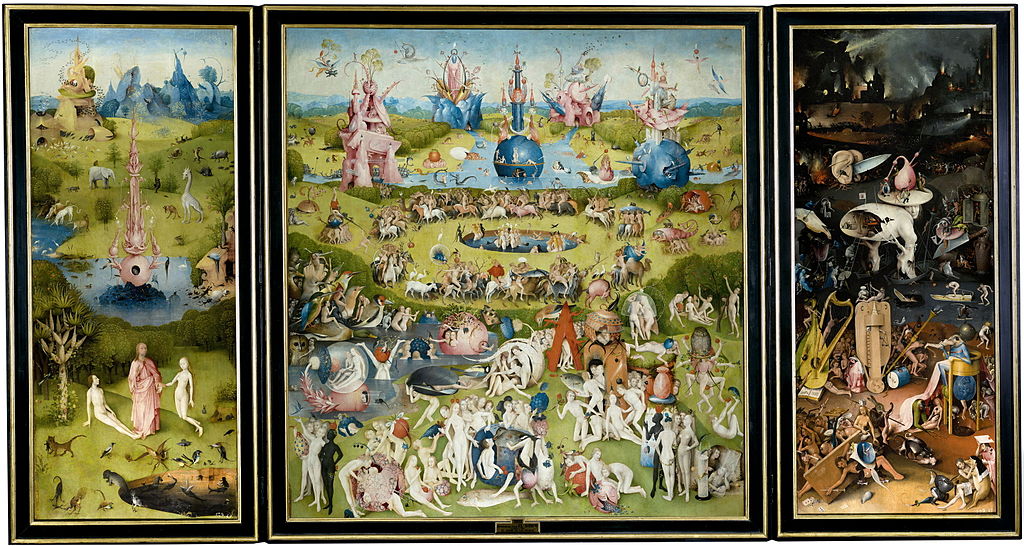

The Garden of Earthly Delights

In the heart of the 15th century Bosch stood at the generational crossroads of art.

Paintings were no longer medieval, but artists had not yet been overwhelmed by the concept of modernity. Bosch was credited with shedding light on the chaos and sins of man’s soul, rather than man’s outward appearance.

His style was so unprecedented in the tradition of painting at the time, there were no rules for him to break.

Bosch (1450-1516) was not simply concerned with personal success but also sought to establish a form of art that had not existed before in the realm of painting – the tradition of craftsmanship remained a stumbling block to the freedom already enjoyed in poetry and literature.

Thomas More’s Utopia would have been a writer’s counterpoint to Bosch’s paradise, published a year after the artist’s death.

Bosch did not paint The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490/1510) for the distrusting eyes of the clergy, disobligingly portrayed in the Hell panel. Making a controversial religious statement was taken seriously at the time, but painting allowed the artist the freedom to draw upon fantasy and religious themes alike.

He reveals the illusory aspect of the way things look in reality, making use of allegorical codes in order to do so

– opening eyes to the abyss beyond the surface of things.

For example, his use of strawberries was interpreted as a symbol for foolishness, inconstancy and fickleness, and furthermore linked to sexuality and sensual pleasures.

Bosch’s use of many varied motifs confused viewers, who had no specific point of reference to guide them to a clear reading.

The painting forced the spectator to gaze upon paradise as though it was an innocent counterworld, in which normal standards of guilt and sin did not apply.

But it was also understood that paradise does not necessarily exist anywhere – it had obviously never become a proven reality. Today, it would be called a virtual world.

He was of course accused of heresy, painting a personal dreamscape rather than any ecclesiastical truths. The exterior of the three-panelled work, with its hinges closed, displays a black and white rendering of the world in its early days, darkness and light, water and earth.

The painting was no alter-piece, but defiantly, almost satirically adopted the form of one. God sits atop a transparent globe hanging in space, pondering his creation. He looks uneasy, referring to the bible on his knee for direction, as if wary about the way his new world is already slipping from his control.

Bosch also enjoyed the role of playing his own God, by inventing many animal hybrids.

World exploration was of great fascination following the recent discovery of America, and the news of many previously unknown creatures was wondrous.

He took pleasure in mimicking the action of creation, and his realistic likenesses of elephants and a giraffe (albeit a silver one) are remarkably accurate; Bosch clearly took painstaking interest in the reported sightings of unknown animals, as well as flora and fauna.

Modern readers of the painting continue to study it to seek out historical insights about the period, reading into motifs for semiotics and searching for literal meaning.

In the left panel, God is seen presenting Eve to Adam.

Adam appears to have just woken from the deep slumber during which God took one of his ribs to create Eve. The position of God’s hand on Eve’s wrist is indicative of him giving his blessing of their union, as Eve looks down shyly.

Was Bosch intending to jibe at the Inquisition’s animosity to all things sensual with this portrayal?

Of the three panels, Hell has been the most widely interpreted and analysed.

Humans exist here, but not in nature; rather, in a civilisation they have created themselves. Cities ravaged by war, taverns full of drunks, manifold torture chambers.

Even musical instruments have turned against mankind.

Humans had brought this blight upon themselves by succumbing to the temptations of the devil. Pleasure becomes torment and music becomes pain – the emphasis on musical instruments intended as symbols of evil distraction.

The lord of the underworld is the bird-headed monster that devours humans and excretes them on his toilet/throne.

The central panel fascinated viewers in Bosch’s own lifetime, and was much copied. It pictures neither paradise nor the earthly world as we recognise it.This prevents the viewer from allocating the scene to any time or place in the biblical history of the world, appealing instead to the imagination.

Naked people indulging in sexual play, an image of civilisation with people moving as naked and freely as the animals in their surroundings, sharing fruit and living in harmony with nature.

His men and women did not possess the self-consciousness that would alienate them from this natural idyll.

It presented a permanent state of adolescent discovery, half child-like curiosity, half sexual liberation. Men riding animals paraded peacock-like to the delight of seductive women, waiting with fruit by a lake.

The fruit does not signify forbidden sexual desire, but rather the natural fertility served by the pleasures of the flesh.

Food is as intrinsic as sex in the image, eating and copulating both represent the nurturing of life. There are no children – people emerge from plants fully formed, sparing the labours of childbirth.

Denying the negative aspects that burden earthly existence,

Bosch creates a vision of unspoilt and immortal harmony.

His protagonists are ageless and lack any individuality. Doll-like bodies, naked souls, their corporeality is effortless, making erotic play seem childlike – a utopian vision of a world that never existed, with inhabitants that are not noble savages, but natural innocents.

Although many artists were greatly indebted to Bosch’s work, none could continue his legacy; this painting in particular can be seen as an interruption in the art history canon. Gone is the innocence of sensual perception which delighted earlier generations of Flemish painters.