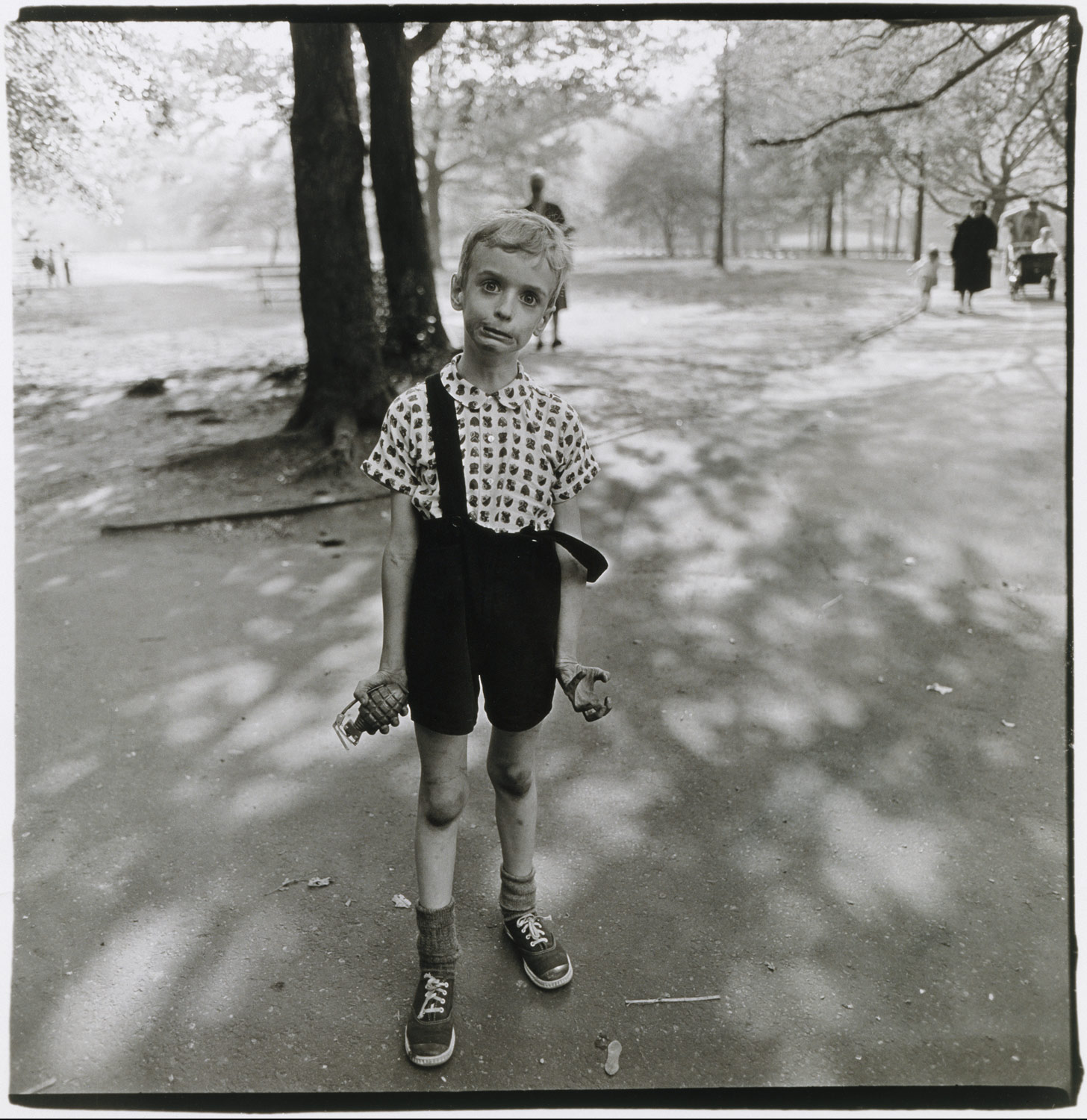

Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park NYC, 1964

Diane Arbus may have had the most congenial, care-free childhood that wealth could provide, protected from the harsh reality of the Great Depression. But you would be unable to tell from looking at her photography.

Instead of capturing picturesque landscapes or fine portraits, she was one of the first photographers to take pictures of marginalised people – dwarfs, giants, transvestites, nudists, sex workers, circus oddballs – and anyone else that was considered to be outside the accepted norm.

Born Diane Nemerov in 1923 to a Jewish couple in New York City who owned Russek’s, a famous Fifth Avenue department store, Arbus was the second of three children, all of whom grew up to be creative. They were raised in a series of lavish homes, but otherwise had a fairly unremarkable upbringing.

However, her mother suffered with clinical depression, and many believe that this, combined with her father being often absent and away working, caused Arbus to separate herself from her background. It probably explains the connection she felt to her outsider subjects.

When her father retired, he took up painting and encouraged Diane to do so too. Not wanting to let the family down, she never revealed her dislike for the medium and continued to study it through summer programs for her parent’s sake. When she was eighteen, instead of going to college she married her young sweetheart, Allan Arbus, who bought her first camera for their honeymoon, and helped turn their bathroom into a darkroom.

Arbus threw herself headlong into photography, enrolling in classes with the great Berenice Abbot. When she became pregnant, she chronicled the entire experience with her camera.

Arbus soon started to photograph models for her father’s store advertisements, which led her to work with Vogue, Glamour and Harper’s Bazaar, alongside other leading names in photography. But despite the success, she grew to dislike this world, and during a spring shoot for Vogue, came to the realisation that she didn’t want any more dealings with high fashion, simply stating ‘I can’t do it anymore. I’m not going to do it anymore’, and promptly turned her back on commercial photography.

Instead, she took to wandering the streets of New York armed with her 35mm Nikon. She would follow strangers, and hover in doorways, until she spotted someone that she felt compelled to photograph. The result was a body of work which was searingly disquieting, yet filled with compassion for its subjects.

Arbus found inspiration and beauty in unlikely subjects, making emotionally-charged portraits of people that were not often deemed “fit” to be in front of the lens of a camera. As she explained “I really believe there are things nobody would see if I didn’t photograph them.” This approach stood on its head the notion that photography was the preserve of the aesthetically pleasing, as opposed to ‘showing the real or genuine world.’

Arbus’ pictures were vilified by many, attracting a number of prominent critics, including vocal feminist Susan Sontag. Although most observers labelled Arbus’ subjects as ‘freaks’, she certainly didn’t. Instead she saw them as people who were, in her eyes, somewhat socially evolved by being different, remarking that ‘most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience’ but that ‘these freaks you call them were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life’.

So contentious was Arbus’ work, when it was displayed at the New Documents exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1967, at the end of each day the gallery staff would have to clean the glass of the photo frames, because members of the public had covered them in spit.

The Museum of Modern Art had acquired her seminal 1962 photograph ‘Child With A Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, NYC’ for seventy five dollars and the Metropolitan Museum of Art bought two other works for similar prices. However, years after her death in 1971, a signed print of the boy with his toy grenade sold at auction at Christies in 2015 for $785,0000.

The child in the image, Colin Woods, was just seven when his picture was taken. At the time, his parents were divorcing and he spent much of his time with nannies. He might look slightly deranged, but years later he said of Arbus, ‘She saw in me the frustration, the anger at my surroundings, the kid wanting to explode but can’t because he’s constrained by his background’.

When Arbus captured those sentiments, perhaps she saw in Colin what she had once felt in herself – the frustration of being trapped by her early environment and unable to express her true feelings, haunted by the guilt of her privilege.

Revealingly, when she photographed a wealthy family at their home in the swanky New York suburbs of Westchester, Arbus spent almost eight hours shooting the family, deliberately employing her ‘truth-by-exhaustion’ technique. It resulted in a cathartic uncovering that demonstrating the stifling nature of traditional domestic roles.

Arbus may have been raised by a respectable and comfortably-off family, but claims about her private life align her more with the subjects of her work than with her upbringing. She once claimed that her favourite thing was to ‘go where I’ve never been’, and friends attest that she did not simply mean in terms of her photography.

There are rumours based on her psychoanalyst’s notes, surprisingly revealed to her biographer in 1984, that she had a prolonged incestuous relationship with her brother for many years. It is also accepted that she would sometimes sleep with the ‘freaks’ she captured on film.

Just as her mother had suffered from depression throughout Diane’s childhood, in turn Diane became overcome by growing melancholy, advancing to the point that she eventually took her own life in 1971 with barbiturates and a razor blade. Her final appointment in her diary read ‘Last Supper’.