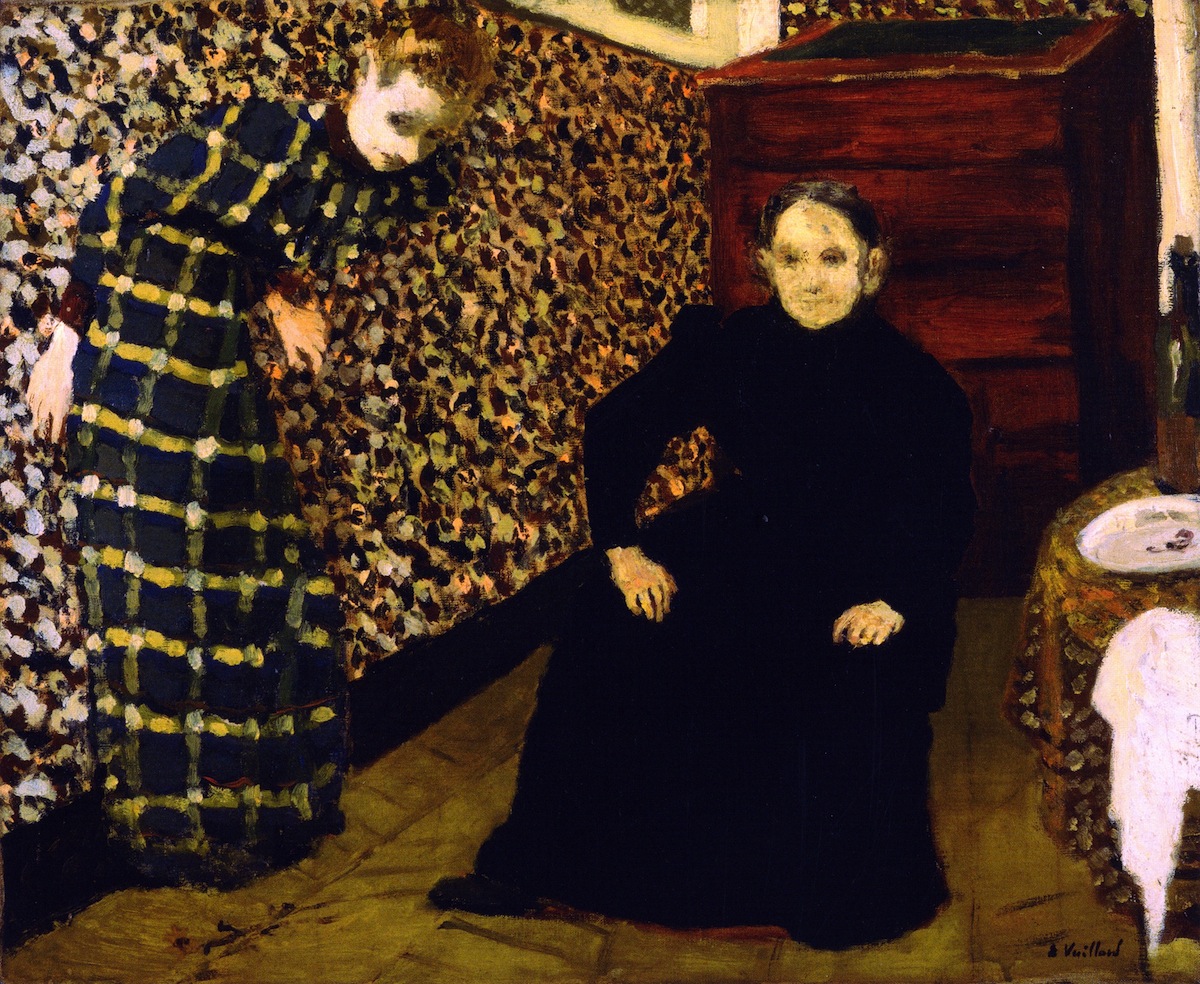

Interior, Mother and Sister of the Artist

It is hard to imagine that Jean-Édouard Vuillard was once dismissed as a painter of ornamental, fussy pictures, simply too pretty to possess any merit at all.

He was born in Cuiseaux, France in 1868, moving with his family to Paris when he was ten. His father was a retired army captain who hoped for his son to follow in his footsteps, and would have been dismayed that his son instead chose to become an artist.

When he left school at 17, he became an apprentice at a minor artist’s studio where he received a somewhat rudimental training in painting.

Vuillard had a number of unsuccessful applications to be accepted at the École des Beaux-Arts, but made it on his fourth attempt after finally passing the entrance exam. It was after he transferred to the Académie Julian that he began to find his feet, meeting Pierre Bonnard and other painters with whom he developed an inspired direction for his work.

The group of young artists, soon to be known as the Nabis, were deeply influenced by Gauguin and Degas, but decided to concentrate on embellished and fractured imagery. They believed that their new technique would emphasise psychological tension in depictions of commonplace domestic subjects.

Highlighting the decorative flatness of their paintings made clear they were more concerned with aesthetics than realism. Vuillard would become greatly admired for his experimentation with texture and pattern, as well as his liberating use of vibrant colour, refreshingly unusual in that era of French painting.

By the time Vuillard was producing his self-portraits in the 1890s, the legacy of Impressionism and its faded pastel shades seemed to belong to the past. His paintings were a manifesto for an unrestricted palette.

In those years he also worked on theatrical set designs and graphics, as did Bonnard, and undertook commissions to create frescoes in apartment buildings.

What set Vuillard apart from his contemporaries was that he lived with his mother until he was sixty-years-old. Although he would occasionally paint streets and gardens, his general subject matter revolved around his home environment, and family.

Vuillard’s mother was a dressmaker who ran a sewing business out of the house. This contributed to Vuillard’s familiarity with decorative and intricate adornment, and they are often included in his paintings. Madame Vuillard was the sole breadwinner for the family after her husband’s death.

In Interior, Mother and Sister of the Artist of 1893, she is seen as the central, highly dominant figure; dressed in oppressive widow’s black, she forms the only unbroken block of colour in the composition.

To the left is Vuillard’s sister, Marie, who appears to be shrinking and almost camouflaged against the wall due to the mingling of the pattern of her dress and the wallpaper. In effect, she seems to be merging into her environment, struggling against the captivity it seems to represent. Even her posture appears to be that of a marionette.

The powerful presence of his mother creates a somewhat menacing and confining atmosphere. Vuillard’s use of flat patterning, and the emotional power of the embedded figure, express a sense of overwhelming claustrophobia, both physical and psychological.

It was Vuillard’s love of literature and drama that also encouraged him to paint his interiors and family as if he were staging a play, blending biography and symbolism.

For many of his fellow artists this appeared an image of hell – trapped in a cage of women. But for Vuillard, who was reticent by nature, it is the world he knew, the world he was accustomed to, and where he felt most rooted and comfortable.

It was Vuillard’s love of literature and drama that also encouraged him to paint his interiors and characters as if he were staging a play, blending biography and symbolism.

This is particularly apparent in his wonderful picture The Suitor, where the female subjects, painted in bright, softly blurred colours, are seemingly involved in intense, quiet sewing, waiting for the theatrical entrance of the central figure. He was later to become his sister Marie’s husband.

In Repast in a Garden, from 1898,Vuillard painted on brown cardboard, leaving the surface untouched in areas, economically creating an understated sense of negative space.

The tightly-woven elements demonstrate his singular ability to manipulate a seemingly idyllic scene with psychological underpinning, as the cobbled courtyard and bushy foliage overwhelm the central figures, painted in muted greys.

The war brought a break in his career and life at home with his mother. He enlisted and became a military artist for a while, capturing the tragic realities he experienced in works such as the remarkable Interrogation of the Prisoner.

When Vuillard’s mother died he was sixty, and he was cared of by his friends and artistic supporters, who helped him through his grief. He eventually recovered his spirit, and was even prepared to accept the role of a man about town, regularly making visits to the theatre and cabaret.

In general, Vuillard was regarded as a likeable man, who inspired affection in those he was close to. He was reserved and quiet, with rare outbursts of emotion. His diary entries reveal that he thought intently about his art, but also agonised over any flaws in his personal conduct, holding himself to high moral scruples.

He never married, but clearly enjoyed the company of women and had many female friends. Women and children were often inspirations for his figure paintings, though he was puzzled why he saw men only as sources of light-hearted imagery, while women were sources of beauty.

In the early 20th-century, while Europe was preoccupied with Cubism and Futurism, many critics considered Vuillard’s work to be too ornate, conservative, and lacklustre.

His work was largely dismissed until decades later – when his radical paintings like Interior, seen here, would be recognised as some of the most luminously sublime creations of the century.