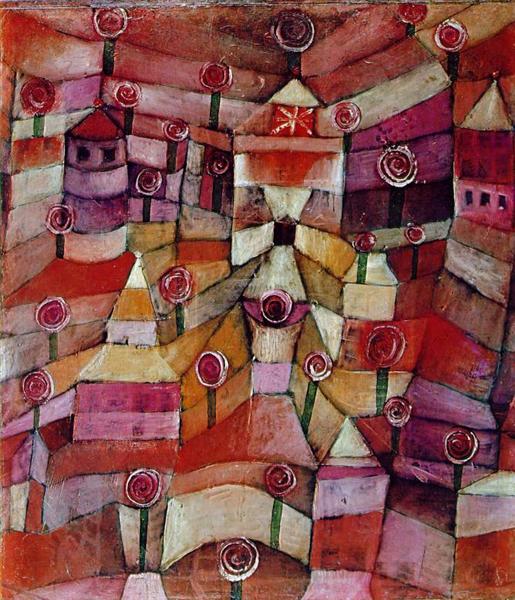

The Rose Garden

It took Paul Klee a long time to find his path as an artist.

Today, he may be seen as a painter with a highly individual style, with a unique approach to composition, shape, and colour; but this was not always the case for Klee.

Many see his works are seen as having an almost child-like appearance, but he laboured patiently for a number of years to achieve that effortless quality.

Klee (1879-1940) was born in Switzerland to respectable but eccentric parents who taught music and singing. They encouraged and inspired him relentlessly, and were soon nurturing his burgeoning talent as a violinist.

He was so accomplished that at 11-years-old, he received an invitation to play with the highly regarded Bern orchestrea. Despite this opportunity, Klee simply couldn’t find the enthusiasm to continue, finding that for him, music lacked fulfilling engagement.

After years of filling his exercise books with sketches, he settled on the idea of becoming an artist when he was in his teens.

He began studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich where he excelled at drawing, but did not have a natural affinity with colour. However despite his insecurity about having the ability to paint well, Klee persisted.

He travelled to Italy to study the work of the great masters of the past. While he responded to the wonderful manipulations of colour surrounding him, he still struggled to find his own feel for it.

Paul returned home to live with his parents in Bern and began experimenting – he drew with needles on blackened glass and created zinc-plate etchings.

He was still dissatisfied, believing that he was not skilled enough to specialise. He divided his time between taking up the violin again, and writing concert and theatre reviews.

Klee then failed in an attempt to become a magazine illustrator, but in 1911 he joined the editorial team of Der Blaue Reiter, the magazine manifesto of a revolutionary new group of an inspiring young artists.

One of the founding members was Kandinsky, and Klee reported ‘I came to feel a deep trust in him. He has an exceptionally beautiful and lucid mind’.

This association with Kandinsky transfixed him with the more modern theories of painting, and quickly travelling to Paris, he was exposed to Cubism, Expressionism, and the early acceptance of abstraction.

Most importantly, he discovered an affinity with the striking use of colour now being used so refreshingly.

He didn’t want to simply echo the exciting work he was seeing, and struggled again to find his own voice; however he was still accepted by his peers, participating in a number of pivotal movements, and met many seminal artistic figures as he made his way.

In 1914 he had a breakthrough when he briefly visited Tunisia, and was so taken by the quality of the light. ‘Colour has taken possession of me; no longer do I have to chase after it, I know that it has hold of me forever…Colours and I are one. I am a painter’.

With that realisation, Klee went headlong into the romanticism of abstraction, utilising his new found vocabulary alongside his draftsmanship abilities.

However, his endeavours were brought to a halt when he was conscripted as a soldier in the forces in Imperial Germany. He lost friends in the war which greatly affected him, and he began creating pen and ink lithographs to express his distress.

He moved around within the army a few times, eventually becoming a clerk for the treasurer until the end of the war. This turn of good luck meant that he could continue painting from his small room outside of the barrack block.

He painted through the entire war, even able to exhibit in several shows, and his work was beginning to sell.

Once the war ended, Klee managed to secure a post teaching at the highly influential Bauhaus school of art, design and architecture. From 1921 to 1931 he was in charge of the stained glass and mural painting workshops, while he continued to experiment and explore colour theory and wrote about it extensively.

His lectures, which were published in English as the Paul Klee Notebooks, were considered to be as important for modern art by his contemporaries as perhaps Leonardo da Vinci’s A Treatise on Painting was for the Renaissance artists.

At the Bauhaus, Klee was once again reunited with Kandinsky, who was also a tutor. By 1932 Klee was at the peak of his creativity, when he is considered to have created his best work and fully developed pointillist style.

He produced almost 500 works in 1933 in his last year before returning to Bern, with his paintings seen as tied to numerous ground-breaking 20th century movements including German Expressionism, Dada, and Surrealism.

But once again Klee was frustrated when he began experiencing symptoms of what would later be diagnosed as scleroderma after his death. The progression of the painful disease can be detected in the last of the art that he created, when he began using simpler, larger designs.

It was in the years following his return from the war, when he started at the Bauhaus, that Klee created his greatest work The Rose Garden.

As a painting it continues to look refreshingly avant-garde even today. Klee’s musical ability comes through as he builds the work, starting with a single motif, in this case the circular roses, and uses it like a music note, building everything around it until a whole symphony is created.

It is a perfect demonstration of Klee’s increasing confidence in the use of colour, as well as his play on perspective and form. The soft lines draw the eyes into the work, the image revealing what first appears to be a two-dimensional picture.

And then it becomes clear that we are seeing a multi-faceted landscape, complete with hillsides, steeples, houses and streets. No painting better reflects his dry humour, and musicality; he stands unique in capturing a convincingly authentic childlike perspective, a grail that has defeated countless artists.