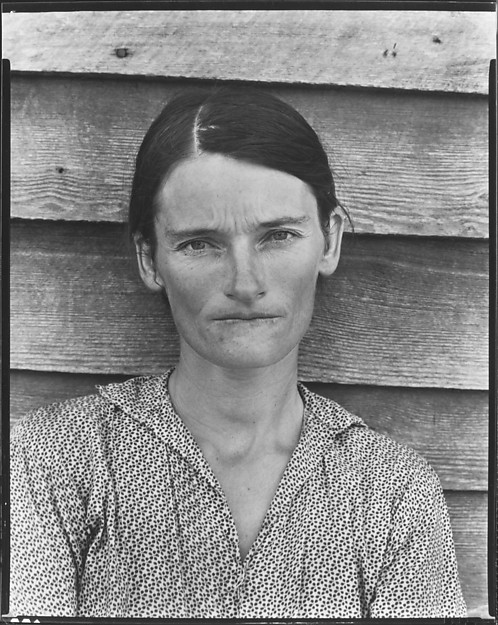

Allie Mae Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama, 1936

A book of photographs spiralled Walker Evans (1903-1975) to totemic status as one of America’s greatest photographers. It was selected by the New York Public Library as one of the most influential publications of the last century.

In 1936, Fortune magazine commissioned Evans to work with writer James Agee to create an article highlighting the impoverished lives of sharecroppers living in Alabama during the Great Depression.

However, the magazine decided not to print the material. The collaboration was subsequently compiled into a book, ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men’ that transfixed readers, and touched America when its words and imagery were widely reproduced.

It unflinchingly portrayed the hardships faced by many families living in utter destitution, resisting the temptation to sentimentalise their intense poverty. Instead, the pictures and writing distilled the deprivation faced across the country into a record of grim determination and dignity.

In the photograph here, the portrait of Mrs Burroughs is characterised by its unfussy composition and clarity. Set against a slatted wooden wall as a backdrop, its powerful horizontal lines highlight her unsmiling gaze. Her brow is slightly furrowed, her lips held together tightly.

It is the enigmatic nature of her straightforward expression which turns her from a clichéd symbol of despair, into a most distinct individual. Her face was to be stamped on America’s consciousness.

In earlier years, Evans had planned to become a novelist and poet; however, once he was faced with a blank sheet of paper, he was immediately crippled by severe writer’s block.

After failing to find any worthwhile work, he moved to Paris and found the atmosphere of intellectual stimulus had a mesmerising effect. Soon, a growing interest in the possibilities of photography consumed him, and despite returning to New York as a fixture within a literary circle, he was quickly spending much of his time taking pictures of the city’s skyscrapers and industrial plants. Evans was fascinated by the work of the brilliant Eugene Atget, the early 20th century pioneer whose unfussy photographs of Paris resonated so personally for him.

Before long, Evans’ work was sought out by publishers, and commissions were arriving regularly. In 1933 he was dispatched to Cuba and it was here that he found he could capture his variety of subjects with a distinctive realism, as he shifted away from the more artistic ambitions of European modernism.

Evans would continue to count upon his reliable, but outdated camera, with its limited lens speed; Atget, his idol, had done the same. He disdained the overly aesthetic, and his forthright approach was clearly demonstrated by his refusal to romanticise the poverty he found across America.

Evans’ photography was accepted by most professional observers as true art, as well as the purest of documentation. He was to inspire a powerful generation that followed, including the great Diane Arbus and Robert Frank.

They would have been struck by pictures like ‘A Graveyard and Steel Mill in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania’, from 1935, with its poetic mastery of this unassuming image.

Dominating the photograph is a large stone cemetery cross, occupying the left half of the composition; beyond we see the modest homes of the steel workers spread out amongst the smokestacks. At the far horizon are the great mansions of the wealthy, a quietly-spoken reference to the class tensions simmering within this industrial city.

In 1938, Evans began his series of ‘Unposed Photographic Records of People’. He would ride the subways with his camera hidden beneath his coat, just the lens peering out, and picture the passengers.

The experiment was daunting even for a skilled photographer like Evans. He was of course unable to use a flashgun, as this would clearly alert his subjects. To compensate he slowed the shutter speed as much as possible, and unable to study what he was framing in each shot, he could only aim for a little luck in the outcome. And naturally, his pictures could only be taken when the train was stationary at stops, otherwise there was too much juddering.

As he explained in a catalogue published in 1962, “Sixty-two people came unconsciously into range before an impersonal fixed recording-machine during a certain period of time, and all these individuals who came into film frame were photographed, and photographed without any human selection for the moment of lens exposure. As it happens, you don’t see among them the face of a judge or a senator or a bank president. What you do see is at once sobering, startling, and obvious: these are the ladies and gentlemen of the jury.”

He subsequently published a collection of 89 subway portraits, titled ‘Many AreCalled’, which accompanied an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

The show was a revelation, as these pictures were seen by his peers as the ultimate demonstration of a purity of technique, largely free from artistic interference. Evans was seen to have discovered, back in 1938, a way to reflect ordinary life in an organic and natural way.

They also admired that these candid snapshots were also a stark rebellion against studio portraiture and the commercialization of photography – no costumes, make-up, props, and posed stances.

What clearer way could he illustrate his belief that contemporary photography routinely focused too heavily on celebrities and politicians? As he showed throughout his career, Evans was truly only fixated by one desire – to convey the realities of his fellow man.