Eclipse of the Sun

You would find it difficult to find an artist whose work was more furious, more profoundly vitriolic, than George Grosz’s.

The only other painter who ever approached his towering rage was Goya, with his pictures that grimly revealed the atrocities of war.

Grosz’s portrayal of life in Weimar Germany in the early decades of the 20th-century are slashingly vicious, and arresting as a withering satirical cartoon.

Grosz (1893-1959) skewered the worst excesses of the political classes in the build-up to Nazism, and the bloated businessmen who profiteered from the nation’s financial woes. His work was laser-sharp at pinpointing corruption and hypocrisy, holding up his cast of subjects to ridicule and contempt. He never used specific individuals, but rather allegorical types that represented the targets of his displeasure.

Unsurprisingly, his views on post World War One German society were considered such disobliging propaganda by the authorities that he was arrested three times and heavily fined in the 1920s.

It was clear that neither George Grosz nor his art were wanted in Germany, and he gladly took up an offer to teach in New York in 1933, just as Hitler was coming closer to totalitarian power.

He had been a leading member of the Berlin Dada group, after having served in the military until he was discharged for being mentally unfit.

His drawings and sketches concentrated on social decay, and the growth of militarism, the gulf between the rich and poor, greedy capitalists, the smug bourgeoisie – as well as hollow-faced factory labourers, disabled war veterans, and the unemployed eking out life on the fringe.

After immigrating to the United States, his work took a less misanthropic turn, though during World War Two his striking painting The Survivor, was considered so offensive by the Nazi regime he was designated as ‘Cultural Bolshevik Number One’.

In reality, once in America, his painting style became more resigned to his lack of faith in humanity, and he seemed content to generally paint attractive landscapes.

He had arrived in America carrying his 1926 painting Eclipse of the Sun and some of his other works, but there was no appetite for his eviscerating pictures in the US. He largely relied on his modest teaching income from various institutions.

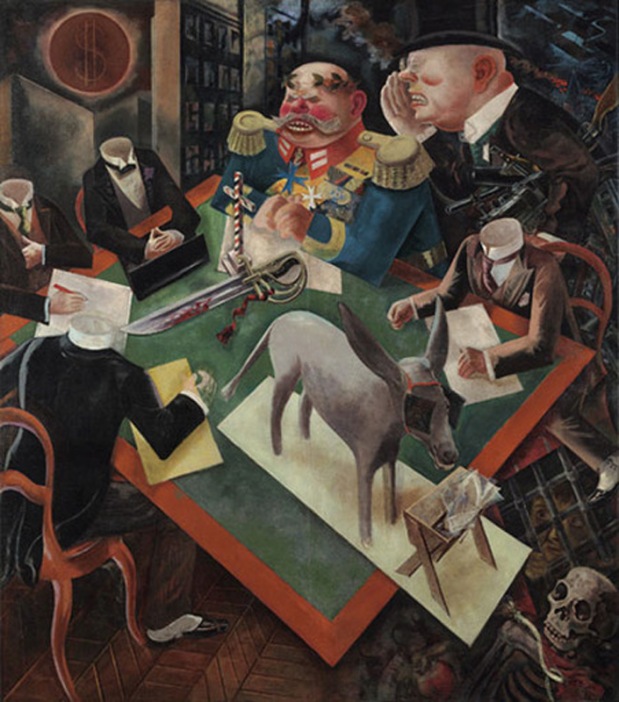

Eclipse of the Sun hadn’t been shown in Germany, because for once its main protagonist was clearly identifiable – the avaricious industrialist and president of the German Reich, Paul von Hindenberg. The painting is a scathing indictment of what we today refer to as the military-industrial complex, with a seated general, and four headless bureaucrats, who are obviously blind to any shady deals taking place.

The artist used the sun as a central symbol of life, eclipsed by a dollar sign as generally accepted representation of greed. The donkey represents a typical self-important burgher, wearing blinders to signify his dumb ignorance. Below, a small child appears imprisoned. Perhaps the child evokes the dissident voice of youth that has been muffled? Or does it simply suggest a brutal lack of concern for coming generations?

When Grosz found himself increasingly short of cash, he parted with the painting to cover a paltry outstanding debt. After his death, the picture was subsequently sold to the local Heckscher Museum in Long Island for $15,000 in 1968.

But in 2005 this small provincial museum decided to offload the painting, to pay for building expansion and general renovations. It appears that over time, the growing significance of the work had become apparent in the art world. They were on the brink of a $19 million sale, when news of the impending transaction leaked.

Protests became increasingly outraged and vocal, and the Heckscher felt obliged to abandon the deal. The museum vowed instead to grant the monumental painting a dedicated prime position, rather than its less ideal earlier placement.

It could now be more widely admired as ‘the museum’s most prized possession’ and ‘one of the most important paintings in 20th century art’.

Even at the height of the First World War, Grosz was creating powerful images that continue to haunt viewers today. The Faith Healers from 1917, also known as Fit for Active Service, shows us a doctor inspecting a skeleton with a makeshift ear trumpet, and declaring him KV, short for kriegsverwendungsfahig, or fit for combat.

The picture refers to the desperate recall of soldiers who had been discharged for medical reasons to return to the front, after German troops had suffered heavy losses.

In A Funeral: Tribute to Oscar Panizza from 1918, his disgust and frustration with the state of German society in the tumultuous post-war years illustrates his sense of claustrophobia. The collage-like technique draws on Cubism and Futurism to present hordes of distorted and skeletal figures in a hellish chasm of buildings leaning precariously over them. The fiery reds and stark blacks create an unsettling tribute to Panizza, the controversial avant-garde author.

Grosz described compositions such as this as a “gin alley of grotesque dead bodies and madmen…. a teeming throng of possessed human animals…. wherever you step, there’s the smell of shit.”

In truth, it is probably more revealing to let Grosz explain his work in his own words: “My drawings express my despair, hate and disillusionment. I drew drunkards, puking men, men with clenched fists cursing at the moon. I drew a man, face filled with fright, washing blood from his hands… I drew lonely little men fleeing madly through empty streets. I drew a cross-section of a tenement house; through one window could be seen a man attacking his wife; through another two people making love: from a third hung a suicide with body covered by swarming flies. I drew soldiers without noses; war cripples with crustacean-like steel arms; two medical soldiers putting a violent infantryman into a strait jacket made of horse blanket… I also wrote poetry.” A leading French critic declared his work “the most definitive catalogue of man’s depravity in all history.” Grosz died in West Berlin three weeks after returning to his native country for a visit in 1956.