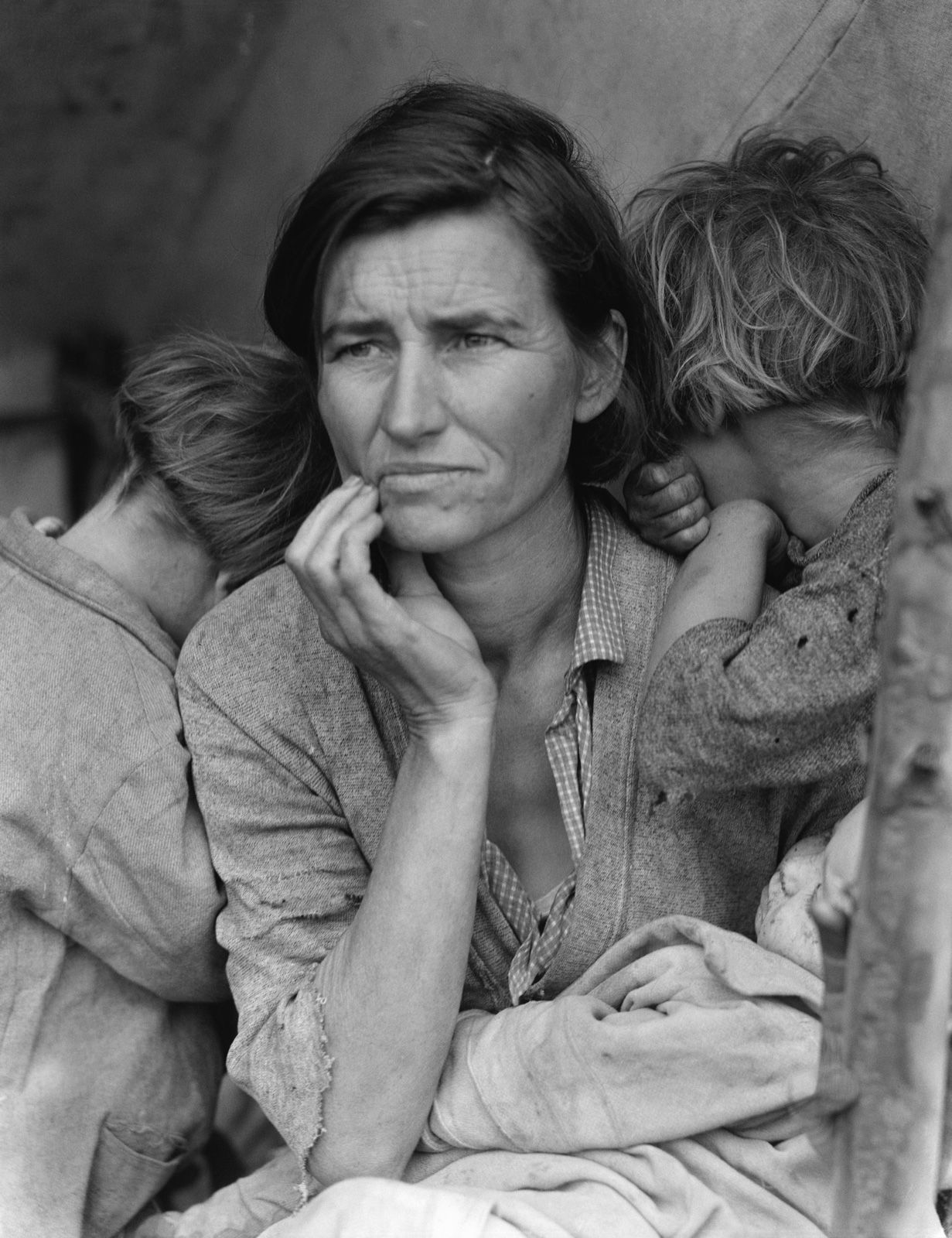

Migrant Mother, 1936

‘Migrant Mother’ resonated so strongly with America during the era of The Great Depression of the 1930s, the image became synonymous with the bleak economic struggle it came to represent.

The experience of shooting it, and its subject, also struck Lange deeply, leaving an abiding impression on her. She described it saying: “I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age was 32. She said they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed.’

‘She had just sold the tyres from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me…I knew that I had recorded the essence of my assignment.”

Of course it was the touchingly poignant expression on Thompson’s face, surrounded by the bowed heads of her young sons that struck the audience so meaningfully. The woman was Florence Owens Thompson, who ultimately lived a full, long life, passing away at 80 years old and with 10 healthy children.

This happy outcome could perhaps be attributed to the success of Lange’s work, as well as the other documentary photographers who worked alongside her, capturing the real human cost of the country’s financial collapse, and spurring change. The Farm Security Administration decided to use any scarce cash available to fund a small band of photographers to reveal their hardships more widely. The aim was to impassionately depict the parlous state of people living in rural areas, hoping to arouse public commitment for social improvement. The campaign was more successful than anyone would have imagined.

They had carefully selected Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), who was to create some of the most seminal images of the time. At seven years old, Lange had contracted polio, weakening her right leg and foot. Obviously this had a profound effect on her life, greatly influencing her future photographic approach. “It was the most important thing that happened to me, and formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me and humiliated me.” Her disability, which left her with a severe lifelong limp, constantly embarrassed her, and observers suggest that her beleaguered subjects offered her greater sympathy.

She had shown little interest in academia and firmly decided to become a photographer as soon as she finished high school. Boldly, she applied to one of the most successful portrait photographers of the country, Arnold Genthe, who hired her as a receptionist.

But he was invaluable in also teaching her the techniques and skills that grounded her work. She additionally was trained to make proofs, retouch photographs, and mount pictures. His sense of aesthetics stayed with her, as did the importance that he placed on high quality reproduction.

Settling in San Francisco, Lange made valuable contacts and connections with business owners and gallery patrons, enabling her to soon open her own successful studio. She married and had two sons, but the dreams began to crack as the Great Depression set in.

Increasingly, she became dissatisfied with her portrait work as she witnessed the effects of financial hardship on people around her. She began to roam the streets to develop her documentary photography skills, experimenting with close-up shots and deceptively simple compositions.

A key early work, ‘The White Angel Breadline’, from 1933, brought about the fundamental change in her outlook. “The discrepancy between what I was working on in the studio and what was going on in the streets was more than I could assimilate”. The image of an elderly man in the mass of people waiting for food in a soup kitchen became particularly symbolic; her use of sharp focus on the texture of his weathered skin and ragged clothes embodied the grimly stark mood of the times.

Using the dynamic compositions of modernist photography, she was able to produce startling and often jarring images of her subjects, offering viewers a subtly moving insight into individual plight.

In ‘Ditched, Stalled and Stranded’, from 1936, she portrayed the haggard anxiety of her subject, seated in a dilapidated car, cropped tightly to increase the sense of claustrophobia, and enhance the impression of harsh truth in the image.

Photographs like this found a home with newspapers and magazines who were concerned with tackling social issues. Lange now found herself primarily a journalist, sharing the suffering she was witnessing in remoter parts of the country, to as wide an audience as possible.

They made an extraordinary impact on millions of Americans, helping them understand the grindingly meagre existence of so many of their fellow countrymen. Her work was soon recognised at home and in Europe as the standard-bearer for generations of campaigning photographers to follow.

Her efforts resulted in her being the first female photographer to receive the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1940. She deferred acceptance twice due to work commitments – the second time when she was asked to document the interment of the US Japanese population following the Pearl Harbour attack. The results of that assignment were deemed so controversial that they were impounded for the duration of the war. Even Lange did not see them for twenty years. But she would always be revered as the most forthright and radical of early documentary artists. And after 80 years her ‘Migrant Mother’ still has the power to reach out and tug at us.