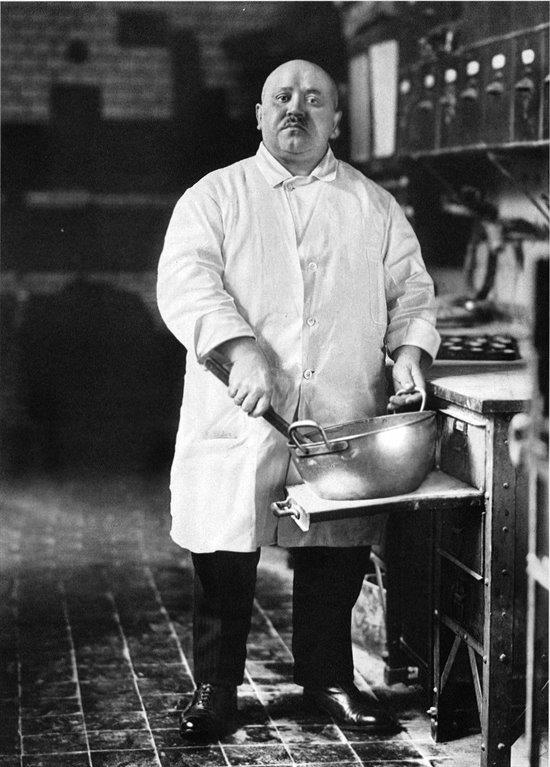

Pastry Cook, 1928

In a monumentally ambitious project that occupied most of his life, August Sander (1876-1967) started taking photographic portraits of his fellow Germans.

From the early 1920s, Sander began creating a comprehensive visual record of German citizens , categorised into seven distinct social categories: ‘The Farmer’, ‘The Skilled Tradesman’, ‘The Woman’, ‘Classes and Professions’, ‘The Artists’, ‘The City’ and ‘The Last People’ (the sick or homeless, veterans etc.) The specific types he covered were his primary subjects for 40 years, which he titled ‘People of the 20th Century’.

He was the first to understand that archive photography could be viewed as art in its purest form. But the photographs were in themselves remarkable, one of the high points in the unflinching realism he introduced in portraiture.

Sander did not grow up in an artistic environment. Rather, his upbringing was somewhat pedestrian. His father was a mine carpenter and later the family would run a small plot of farmland. It was during his time spent at the local mine, helping to carry the company photographer’s equipment, that Sander discovered the medium that immediately transfixed him.

After he had completed his military service, he worked as a photographer’s assistant, before he was skilled enough to eventually set up his own photography studio in Cologne – and his portrait documentation was to begin.

Sander’s deft analysis that he brought to bear in treating his subjects provided a revealing insight into the character and lifestyle of each of them. His masterly technique using this typological approach created simple images of electrifying power. Such power, in fact, that the Nazis didn’t approve of much of the work. Sander had included marginal members of the populace – gypsies and the unemployed – that did not mesh with National Socialist ideals of Aryanism.

In 1936 The Nazis confiscated the first published volume of the series, ‘Face ofour Time’, and destroyed all of the printing plates.

Some years later, Sanders moved from Cologne to an isolated part of the countryside, and was able to take his remaining 10,000 negatives that were not found by the authorities. Seen here is ‘Pastry Cook, Cologne’, which he had shot in 1928, a triumphant example of the immense precision he was able to capture in a routine portrait. Direct eye contact with the hefty chef in his kitchen allowed the viewer to get a genuine sense of the man. His confidence and authority make clear that this is no set-up façade; instead it is an unemotional interpretation of a man going about his work preparing food.

In the subtle composition, the curves flow from the chef’s bald head, to his rotund belly, and onto the round steel bowl in his hands.

What makes the picture so splendid is Sander’s use of light. The chef is well illuminated, with his face and body equally exposed. The background is dark and out of focus, emphasising the impact of his gaze.

Sander used streaks of light across the floor and background wall as highlights, to stop the image being seen in a black abyss. This small hint of a light brings the environment to life. It is revealing to note that Sander’s categories of portraits evolved into subcategories, often adding a filing subtitle to each image. This chef belongs to Skilled Tradesmen, but also Widowers.

Similar lighting techniques were used in his picture, ‘Bricklayer’s Mate’, 1928. The strong contrasts, coupled with the confrontational stare of the young subject, and the evident weight of the bricks that he carries on his shoulders, create a depiction that is both proud and informative.

Sander explained ‘The portrait is your mirror. It’s you’, demonstrating his belief that photography could reveal the characteristic, inherent traits and essence of people. He often described himself as simply assisting a self-portrait, rather than considering himself a pure artist.

Humanity was his subject, and he found it wherever he looked, affording each and every individual equal respect and dignity – a mammoth task that consumed him for his entire adulthood.

This refreshing attempt to portray real life had a mesmerising impact on the avant garde Neue Sachlichkeit – new objectivity – group of artists emerging Germany in the 1920’s, who were strongly reacting against expressionism. They were deeply struck by Sander’s insistence that ‘nothing is more hateful to me than photography sugar-coated with gimmicks, poses and false effects. Therefore, let me speak the truth in all honesty about our age and the people of our age’.

In later years, he would continue to be a source of inspiration to outstanding American photographers Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Diane Arbus, who each acknowledged their debt to Sander’s trailblazing rigour.

Sander’s legacy still resonates today, with many conceptual artists captivated by his pioneering obsession with documentation. Germany in particular has produced the emphatic work of revered contemporary photographers Berndt and Hilla Becher, with their extensive series of deliberately stark pictures of industrial buildings and coal mines, taken over a thirty year period.

Similarly, much admired Thomas Ruff has also spent decades taking large-scale portraits of random individuals, that appear to be vast enlargements of standard passport snaps. They pack a surprising punch, but Ruff would be the first to admit that Sander did it much earlier, and much better.

Unsurprisingly, August Sander is generally regarded as one of the greatest German artists of the century.