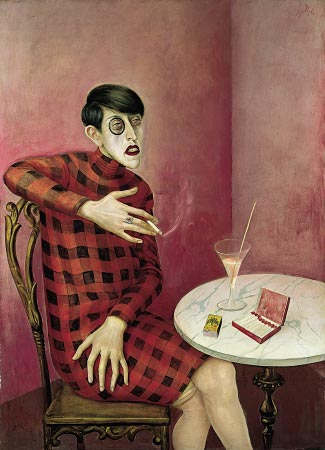

Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden

Berlin in the roaring twenties, and painter Otto Dix chases writer Sylvia von Harden down the street proclaiming: ‘I must paint you! I simply must! You are representative of an entire epoch!’

Von Harden, surprised, coolly responds: ‘So, you want to paint my lacklustre eyes, my ornate ears, my long nose, my thin lips; you want to paint my long hands, my short legs, my big feet – things which can only scare people off and delight no-one?’

Sylvia von Harden was, other than caustic in her self-evaluation, a journalist, short story writer and poet who particularly represented the avant-garde Neue Frau, a New Woman in Weimar Germany. She was thirty-two years old at the time of this painting, pictured here in the Romanisches café in Berlin.

This daringly bohemian hangout for writers, artists, models and intellectuals was considered by more respectable citizens to be the ‘headquarters of the world revolution’. Dix happily spent much of his time there.

Von Harden was clearly a woman of striking tastes; with a pink cocktail matching pink tipped cigarettes and large ring with a pink stone, in her portrait she seems to be gesturing as if bored by the dull conversation. The neue frau is not typically feminine and von Harden rebels by wearing her hair in a daringly close-cropped ‘bubikopf ’.

Selecting to wear a figure-disguising dress with a strong geometric pattern, her monocle and her large hands add to her androgynous statement. Dix presents a woman who is overturning cultural and gender stereotypes, her sagging stockings suggesting that she has other things on her mind than appearing prim and pristine at all times.

Dix (1891-1969) said of his choice to paint von Harden, ‘You have brilliantly characterised yourself, and all that will lead to a portrait representative of an era concerned not with the outward beauty of a woman but rather with her psychological condition.’ In this portrait, as with much of Dix’s work, realism is pushed almost to the level of caricature.

While she was clearly considered amongst the intellectual glitterati, all documentation of her life and work suggests she spent more time chatting in cafés sipping on cocktails and dragging on cigarettes than doing any actual writing.

She wrote a literary column for the monthly Young Germany, and published two volumes of poetry in 1920 and 1927, but she generally managed to make ends meet by writing leaflets and reviews.

Most of her output was judged harshly by the bourgeoisie who found them to reveal a ‘whore’s sentimentality’ they found deeply unappealing.

Dix generally only made studies and cartoons of his sitters, and would then work in his studio on the final painting. Von Harden revealed that her portrait began with a much more detailed preparation process: ‘For three weeks I sat for a few hours every day. This might be easy for a professional model, but for me it was rather strenuous. When I saw the finished portrait on his easel and had to look at my long face, the somewhat affectedly spread out fingers, and red and black checkered shift, and the short legs, I realised Dix had created a very strange painting, one that gained him much recognition, but also much criticism.’

By the time that Dix painted von Harden in 1926, he had become somewhat notorious as the angry, handsome young man that everybody loved to hate. He was receiving commissions from people who found it a privilege to be painted in his flaw-celebrating manner.

His own taste in sitters was for people like Sylvia, and others living on the borders of social acceptability – prostitutes, show girls and drug addicts featured among his favourite subjects.

In 1925, Dix moved to Berlin, which was in the grip of astonishing inflation, when $1=14 million deutschemarks. The city, and the painter, became heavily influenced by American culture when the U.S.A swooped in to bail out Versailles-treaty crippled Germany.

Dix revelled in the American spirit, finding it an appropriate outlet for his rebellious nature. He adored visiting cinemas showing American movies, and dancehalls playing American music – he was a great dancer and gained the nickname ‘Jimmy the Shimmy’.

Writer Ilse Fischer wrote in her profile of Dix that his appearance was striking, with ‘the smoothly combed blond hair of an American, dressed in the American style, the cut of his suits with exaggeratedly wide padded shoulders, short trousers, and an unnaturally high waistline.’

He was undoubtedly a somewhat vain man, who produced many self-portraits, kinder to himself than to most of his hapless subjects. He often declared, ‘either I’ll become famous or notorious’, and he managed to achieve both.

Berlin in the 1920s was a vibrant metropolis, frequently cited as providing ‘the highest level of intellectual production in human history’. Certainly, Germany at the time was considered by many as the country with the most advanced science, technology, literature, philosophy and art.

His ideas and style gained him both many admirers and detractors. Ilse Fischer also said of Dix: ‘he falls between the classes, outspoken critic of the bourgeoisie, but he also can’t stand the working class – unrefined, herd mentality, narrow minds. He’s an outsider. He attacks his subject, whatever it might be, violently and impulsively. He dismembers and dissects the naked object with the lustfulness of a sex murderer. But like the psychopath… he leaves the scene of the crime feeling sobered and empty.’

The Nazis were not enamoured by Otto Dix and included him in their Degenerate Art Exhibition, banned him from exhibiting elsewhere, even burning some of his paintings.

He was also dismissed from the Dresden Academy and the letter sacking him read: ‘your paintings are a gross offence to moral feelings. You’ve painted pictures liable to undermine the German will to defend itself ’.

When he applied for professorship at Stuttgart Academy, they wrote back, insultingly asking for examples of his work as if they had never heard of him, and denied him the position.

He retreated to Lake Constance and spent the rest of his life there, feeling exiled.

He had lost his subject matter of stimulating portraiture, and started painting landscapes, never fulfilling again his artistic needs, so focused on society and unorthodox people.