Spanish Night

Francis Picabia lived a somewhat charmed existence, never having the stresses and woes of everyday life taking their toll, allowing him to explore whatever area of creativity took his fancy from one day to the next.

Born in 1879 in Paris to wealthy parents, his father was a Cuban diplomat with a prosperous sugarcane plantation, his mother an heiress to a mercantile fortune, who died when he was a seven-year-old.

He was brought up by his father, maternal grandfather and an uncle. Their home was known as the house of quatre sans femmes (four without women).

It was his uncle’s love of art that first sparked Picabia’s own interest, and young Picabia grew up surrounded by classical French painting. His grandfather was a skilled photographer, who introduced the boy to the medium.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, none of the figures in his life objected when he considered becoming an artist, enabling him be educated in art academies and trained in painter’s workshops.

Picabia’s wayward behaviour began early on, when he started to copy pictures in his father’s collection, swapping the fakes for the originals, which he then sold. As he explained ‘when no one had noticed, I discovered my vocation.’

By the age of 21, his family’s financial backing allowed him to set up his own studio, but his talents soon earned enough to buy his first car, a passion which eventually saw him owning a hundred different models during his life. Throughout his 20s he found recognition with his Impressionist landscapes, which he often simply appropriated from postcards, managing to shock die-hard plein air artists such as Pissarro.

Success came to him as easily as did his family’s support. He never sensed the urgent need that other artists routinely endured – having to sell some work in order to survive, or taking paying jobs on the side.

Picabia is often described by those who knew him as a sceptic, and over-influenced by Nietzsche’s nihilist philosophy. This probably explains why throughout his career he had associations with so many different ground-breaking movements, but was never totally affiliated with just one.

In 1907, Picabia had joined the avant-garde, switching between faux Fauvism, a mashup Cubism, then trying his hand at a little abstraction, before finally committing, as much as he knew how to, to Dada.

In fact, despite his tendency to flit between movements, Picabia is considered an early founder of Dada, and in both the UK and France he is known as ‘Papa Dada’.

This new direction allowed him to abandon many of the technical concerns that had been apparent in his previous work. Instead he began to use text and collages to create imagery that attacked conventional beliefs on morality, religion and law. Picabia’s use of differing mediums varied wildly, with his work described as everything from audacious, to irreverent, to scandalous.

This light-hearted approach to both society’s values and art in general often left Picabia at odds with his more respected peers, who were less cynical about the importance of art-making. He simply lacked any resolute confidence in the ability of art to influence or improve the world.

It seems clear that Picabia was an artist with little respect for any conventions, a man who never had to answer, or really commit to, anything.

After tiring of Dada, his art grew even more extraordinary, with his ‘monster’ paintings of the 1920s. Using commercial paint in shockingly gaudy colours, the figures in his paintings became increasingly disturbing, as well as somewhat entertaining.

His subjects were sometimes indistinguishable as either male or female; faces would feature one central eye, or several rows of multiple eyes. At best they were seen as the creations of a troubled mind, or the result of a reliance on hallucinogenics.

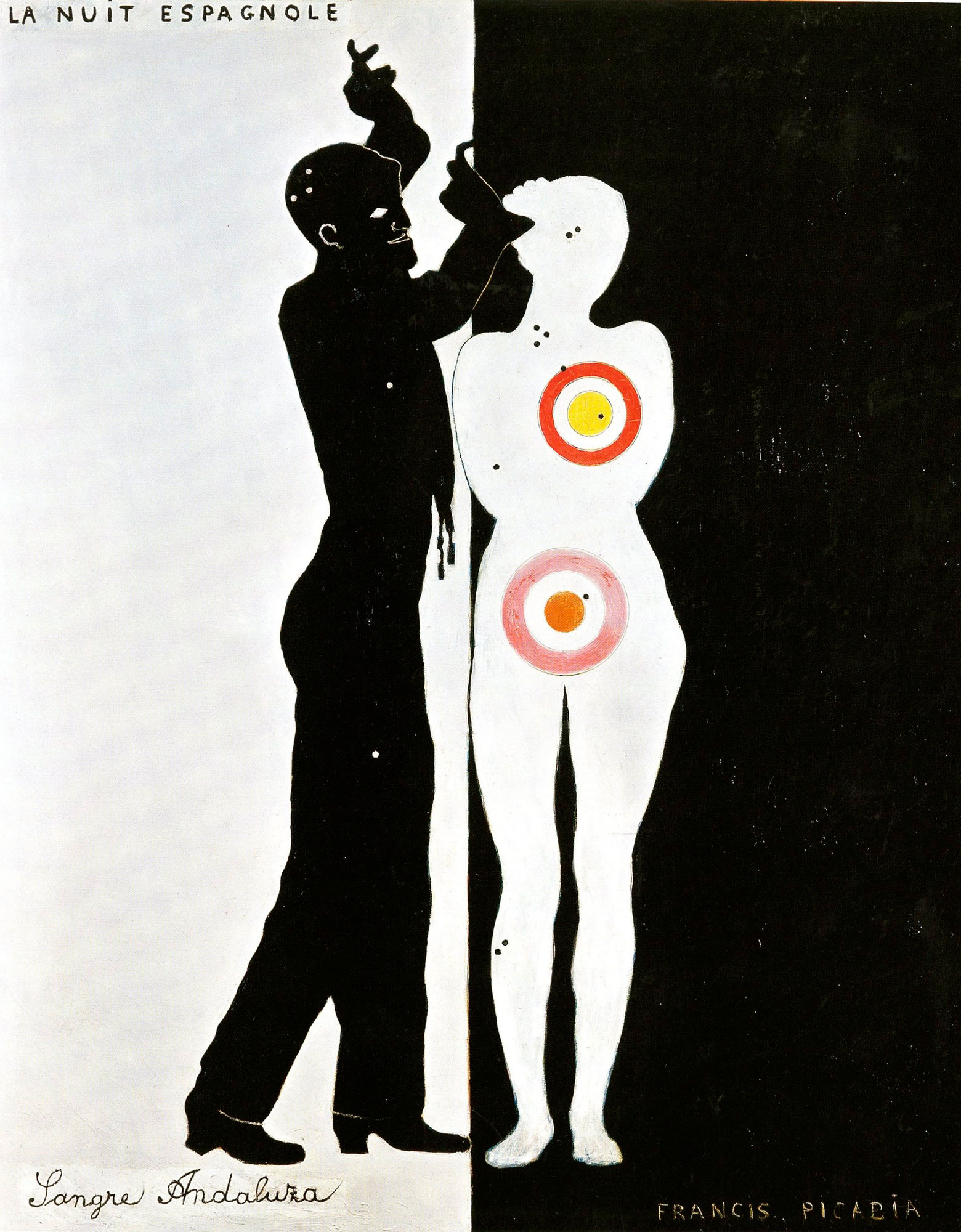

Spanish Night seen herewas produced at the same as his more bizarre creations. This large, boldly graphic work shows the influence of earlier times when he enjoyed working in commercial illustration and graphic design. With his use of black and white enamel paint, Picabia clearly wanted the painting to be as visually impactful as possible.

A classical female nude is seen standing in silhouette on the right, marked with targets at her erogenous zones. Both she and the black-shadowed male beside her are scattered with small bullet holes. The figures appear as cut-outs on the otherwise blank shiny surface.

The work was referred to as ‘Andalusian Blood’ perhaps to heighten the erotic charge of the image. After decades of experimentation, this remarkable work marks a transcendent return to a more figurative approach in his paintings, deeply unconventional as they were. He would regularly turn to multiple-layered imagery to heighten the tension he aimed to convey, in his much admired series of Transperance paintings

For about 20 years, figuration became central to Picabia’s work and he would often try to amalgamate conflicting sources. He drew on works from the Romanesque and the Renaissance, as well as the cheerful naked ladies found in photos in girlie magazines.

His garish images of statuesque nudes from soft-porn publications were certainly more confrontational than traditional paintings of the female form; many of them were sold by an Algerian merchant, ending up decorating brothels.

This troubled Picabia not a jot. He aspired to an art that would be ‘unaesthetic in the extreme, useless and impossible to justify’. He had little regard for what anyone thought of what he produced, a sentiment compounded when he stated that ‘My ass contemplates those who talk behind my back’.

He was a reckless character, who was easily bored, and once wrote; ‘I play baccarat and I lose, but more and more I love this empty and sick atmosphere of the casinos’.

Perhaps most revealing about his viewpoint on art, Picabia matter-of-factly explained that ‘if you want to have clean ideas, change them as often as your shirt’. In numerous ways, Picabia became one of the most unlikely artists of the 20th century to achieve greatness. His power is still not fully appreciated today, though with each new generation of artists, his presence and influence grow ever more pervasive, as Spanish Night escalates to totemic status.