The Death of Marat

All great revolutions need a signature image, a totemic piece of visual propaganda so vivid it stirs fervour in the hearts of the proletariat, and makes heroes and martyrs of their leaders.

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), France’s leading artist of the day, was profoundly certain that he was the man for the job. And his extraordinary painting The Death of Marat did indeed become the most electrifying symbol of his country’s most tumultuous era.

It is fair to point out that David’s political compass was flexible, or more kindly, pragmatic; his affinities, and his paintbrush, shifted ably with the political horizons.

His diplomacy at serving many masters, without losing his status as France’s leading artist, or indeed his head, was something of an achievement during the turmoil of the French Revolution.

Born to a wealthy family and transferred to his uncle’s care once his father had been killed in a duel, David was highly educated. But he would always prefer to be sketching rather than applying himself to architecture as his family wished.

Perhaps the severe facial tumour he suffered from, making his speech laboured, gave the solitary nature of making art more appealing.

David became renowned for launching the emergent Neo-Classical style. Like a thunderclap, he presented his overwhelming painting The Oath of the Horiatii, which transfixed Paris in1784.

This epically-scaled tour de force was a dramatically radical departure from the frills and finery of the Rococo style that had so dominated French art.

David depicted classical images from Greek and Roman lore, with the clean lines, clarity, proportion, and the musculature of ancient statues of the Greats. The aesthetic choice was not incidental – stylistically and thematically the painting endorsed the rising political tide of Republicanism in France.

As the Reign of Terror held the nation in its grip, David found himself at the fulcrum of the Revolution as a member of the Jacobin party – and a friend of its powerful conductor, the fearsome Maximilien Robespierre.

David’s rebellious zeal at this time was not unconnected with his artistic ambitions; the strictures of the establishment Academy, and their traditional stranglehold on the ‘appropriate’ style, content and technique of painting, were a source of his ongoing frustration and fury.

He had applied for the Academy’s Prix de Rome scholarship four times as a youth and failed three of them, leading him even to attempt starving himself to death in protest, until he was finally accepted in 1774.

But now David’s power was in the ascendancy; he served as a member of the Committee for General Security, signing over 140 arrest and death warrants, and in 1793 was one of many who voted for the execution of King Louis XVI, an event that sent shockwaves across Europe. It also led to David’s divorce from his Royalist wife.

As it transpired, the last image of a frail looking Marie Antoinette before she went to the guillotine was a sketch made by David.

David was also effectively a Minister for Propaganda, organising and planning many civic events which glorified moments of the Revolution’s highpoints.

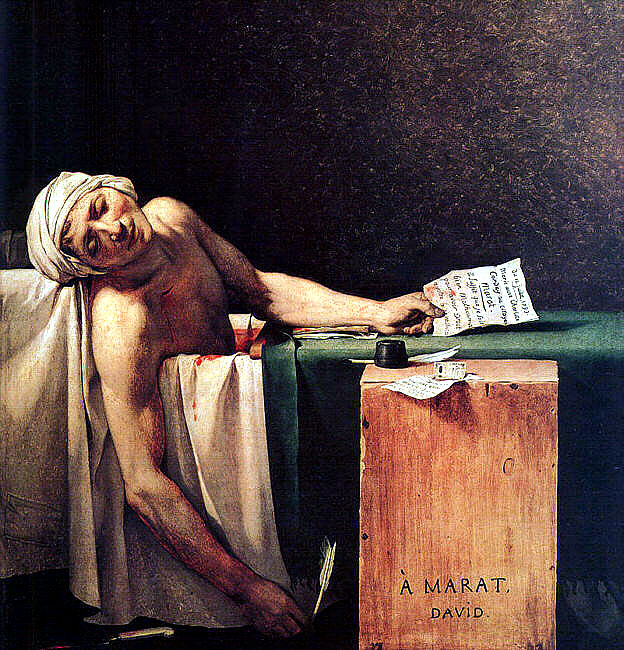

His remarkable The Death of Marat, 1793,still remains an iconic French symbol of the Revolution. Originally, David had been commissioned by the National Convention, directly after the assassination of his friend Jean-Paul Marat, a prominent revolutionary journalist, scientist and doctor.

The composition draws from Renaissance images of the dead Christ. David was a particular admirer of Caravaggio, whose use of deep of shading and contrast were so riveting.

In David’s picture the scene is distilled and dramatized, especially the treatment of Marat as a marble-skinned corpse. Marat is in the bath because he suffered from an intensely itchy skin disorder that caused rashes and lesions.

It led many to compare Marat’s diminutive, somewhat unattractive figure to that of a toad. The only way for poor Marat to relieve his symptoms was immersion in various ointments, with a turban soaked in vinegar around his head.

As a result, when his assassin Charlotte Corday came to call, he granted her an audience, against his wife’s protestations, in his bathroom.

Corday had promised him a list of secret enemies of the Revolution she was prepared to betray. She sat next to him and started reading the names, then suddenly rose from her seat and buried a knife into Marat’s chest.

In the painting the knife has been removed and lies on the floor, and all that is left of his assassin is the paper list Marat holds in his dead hand. Ironically Marat by this time had fallen largely out of favour with Robespierre, and was seldom invited to matters of the state, so Corday had essentially targeted a political outcast.

Despite this, Marat was lionised by the Revolution after his death, his ashes were interned at the Pantheon, and the Marquis de Sade gave him a eulogy. His remains, and the various busts of him that peppered French cities were, of course, later to be removed.

David’s painting had certainly became immediately celebrated, to the point that he later had to take great pains to hide it from authorities when the Revolution collapsed, and Napoleon came to power.

After his death it was never displayed publicly for decades to avoid enraging the public.

David’s eventual fall from grace had quickly followed after Robespierre’s, and led to his imprisonment. However, while in jail he conceived his magnificent painting The Intervention of the Sabine Women.

The picture is often read as an appeal for forgiveness after the bloodshed – and a testament to his ex-wife who visited him in prison and campaigned for his eventual release. They were to soon remarry.

Fortunately, the painting earned the attention and admiration of Napoleon. David went on to create some of the most memorable depictions of Napoleon, including his coronation and passage through the Alps – all despite having been a signatory to Empress Josephine’s first husband’s execution.

As can be seen, David’s approach to painting traversed neatly alongside his shifting political affinities, making him possibly the most dexterous propagandist in art history.