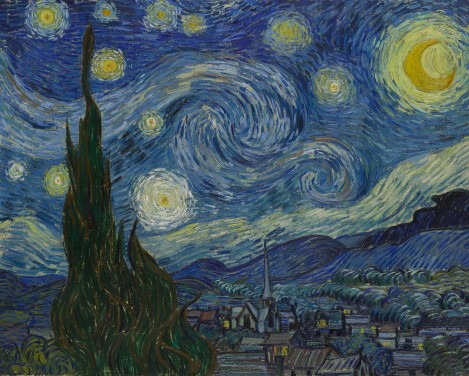

The Starry Night

When Van Gogh (1853-1890) hospitalised himself at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, an asylum and clinic for the mentally ill, he was allocated a studio and was also allowed to paint in his bedroom.

This provided an extensive view of the mountain range of the Alpilles: it was here that Van Gogh painted Starry Night in June 1889.

Van Gogh saw the night as ‘even more coloured than the day’ and obsessively waited for the perfect night sky. Interestingly, Van Gogh had originally planned this work as a pendant piece

Paul Gauguin was in charge of organising an art exhibit for the 1890 World’s Fair shortly after Starry Night was completed, and Van Gogh wanted it to be displayed alongside its daylight companion, his Wheatfield with Cypress – a representation of the landscape of Starry Night at midday.

Even though the sun is not visibly included, the brightly painted and shadowless wheatfield suggest the overhead light of noon.

Van Gogh’s paintings weren’t included in the show in the end.

Van Gogh had been fascinated by Delacroix’s use of colour, especially of the two colours he described as ‘most condemned, and with most reason, citron-yellow and

Prussian blue.’

He felt Delacroix ‘did superb things with them’ – and inspired his palette for Starry Night. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam has recently revealed that the hues originally painted by Van Gogh in the1880s have actually faded, and what we see today are pale echoes of the original colours.

Of course, it remains an electrifying painting, composed using elements of a few previously completed works still stored in Van Gogh’s studio.

He envisioned his ideal Starry Night over a landscape and not over a town. He wanted it to be not merely a descriptive piece of work, but an amalgamation of aspects from imagination and memory.

He depicted a cypress and a village rather than the enclosed field beneath his bedroom, and these are seen in the sketches he had previously drawn.

The bird’s eye view in the painting highlights the vastness of space and time. Harvard Professor Charles Whitney noticed a stylised but striking similarity between the painting and the swirling star configurations and scientific drawings of spiral nebulas that had been published and widely discussed in France in the late1880s.

He also found accurate portrayals of the Milky Way, Aquarius, crescent moons and other star patterns in a number of Van Gogh’s other paintings.

Van Gogh incorporated an important revision from the detailed ink study of the Starry Night to the final painting; to allow for the addition of an eleventh star, he reduced the cypress tree.

In his younger years, he wanted to dedicate his life to evangelising for those in poverty. This exact number of eleven stars was significant to Van Gogh’s powerful religious conviction; they held an important link for him to Genesis

37:9, and a favourite phrase he often referred to: ‘I had another dream, and this time the sun and moon and eleven stars were bowing down to me.’

In 1890 Van Gogh moved to Auvers to be near his physician Dr Paul Gachet, who lived there and had agreed to look after Vincent.

When he had first met Gachet, he was initially impressed, but soon became doubtful of his competence and commented that Gachet was ‘sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much.’

However, he and the doctor became great friends, and Van

Gogh was drawn to his obsessive passions for homeopathy, electroshock therapy, and anthropology.

He painted numerous portraits of Gachet, one of which sold at auction in 1990 for over $80 million, a world record at the time.

(Vincent only ever sold one painting in his lifetime, the wonderful Red Vineyard, to a wealthy artist friend for 400 Francs, about £750 today. The picture is now owned by the Pushkin Museum, in Moscow.)

He regularly told his brother and sister that he found Gachet’s mental instability similar to his own, and identified with Gachet’s avid involvement in his work as his way of easing loneliness and melancholy.

He also praised the doctor for having ‘good knowledge of what is being done these days among the painters’, and liked the fact that Gachet himself drew and made engravings to help him maintain his balance.

He also added, ‘Unfortunately it is expensive here in the village, but Gachet tells me that I can pay him in pictures, and I could not do that with anyone else if anything happened and I needed help.’

The same day he wrote to his brother Theo mentioning that although Gachet seemed very sensible, he was ‘as discouraged about his job as a country doctor as I am about my painting’ and that Van Gogh offered to ‘gladly exchange job for job. If the depression or anything else became too great for me to bear, he could quite well do something to diminish its intensity, and that I must not find it awkward to be frank with him. Well, the moment when I shall need him may certainly come, however up to now all is well.’

It is still unknown why Van Gogh did eventually decide to commit suicide, at just thirty-seven.

Gachet proposed to give a eulogy at the funeral, but struggled as he wept profusely and eventually stammered a very confused farewell. He was attempting to outline Vincent’s achievements, praise the honesty of his work, and point out that the fact that he prized art above everything, and that would make his name live.

It was Dr. Gachet who had summoned Theo after Van

Gogh had shot himself. The doctor had striven hard to save Vincent’s life but his efforts were eventually in vain.

Shortly after Van Gogh’s death, Gachet wrote to Theo: ‘The more I think of it, the more I think Vincent was a giant. Not a day passes that I do not look at his pictures.’

Van Gogh joins the ranks of many artists whose lives have been made into biopics by various Hollywood studios, including Michelangelo, Vermeer, Gauguin, Turner, Basquiat,

Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec, Pollock, Modigliani, Goya,

Caravaggio, Gentileschi, Renoir, Munch, Rembrandt,

Warhol, O’Keeffe, Klimt, da Vinci, Rockwell, El Greco,

Bacon, Kahlo, and Matisse.

Van Gogh is alone in having three films devoted to his life, in which he is played by Kirk Douglas, Tim Roth and Jacques Dutronc.