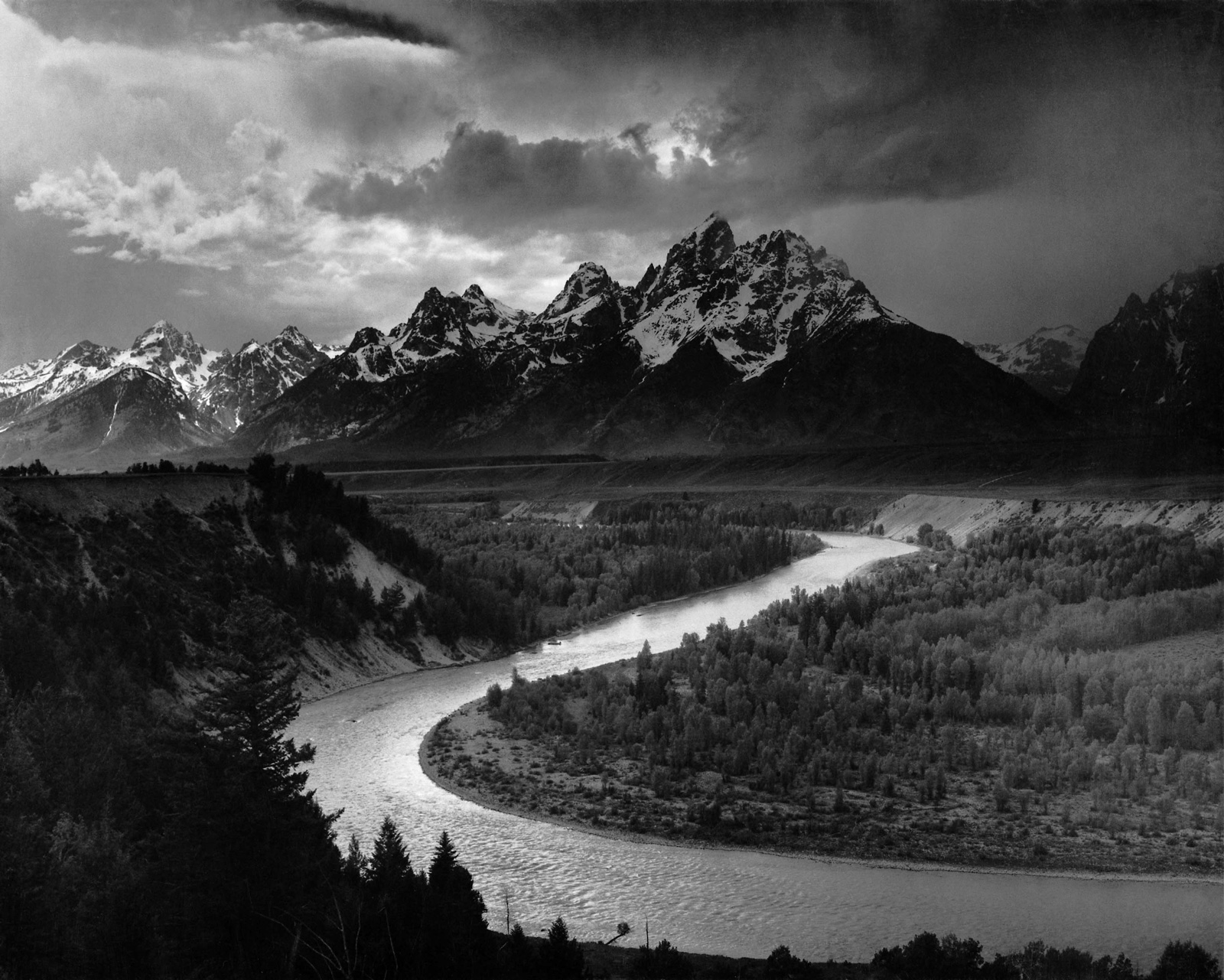

The Tetons and Snake River, 1942

Ansel Adams (1907-1984) is widely considered the greatest landscape photographer of the 20th century. If you are an admirer of film director John Ford’s westerns, with their panoramic vistas of America’s Monument Valley, it was Adams’ photography that inspired these striking backdrops.

Adams obsessively documented the vast untouched deserts around Utah and Arizona, but had an abiding love for the Yosemite Valley, and in particular the High Sierras. Working with a variety of large-print cameras and black and white film, his sublime pictures transfixed viewers. Americans were largely unaware of this magnificent wilderness that some may have heard about but few had ever seen.

His career was dedicated to revealing the raw beauty of unspoilt parts of his country. He found that working on these photos such an overwhelming experience, it would transform him into a staunch conservationist – becoming a seminal figure spearheading the environmentalist movement. Adams was a tireless advocate for the protection of the wild prairies he was so beguiled by, and campaigned vigorously to maintain them as national parks.

Prior to Adams, pictures of the American landscape were predominantly associated with the Hudson River School of painters, working in the mid-19th-century. Their pictures were generally disparaged at the time as being over-sentimental, wistfully idyllic tableau.

Adams felt that advances in photography could serve as the perfect means to capture the majesty of nature, far more effectively than paint and canvas. He was introduced to taking photographs at 12 years old when he was gifted a Kodak Brownie camera on a family trip to the Yosemite. It was to be a gift and a trip that were the beginning of a lifelong love affair.

Ansel returned to the Yosemite the next year, exploring the High Sierras during summer and winter, quickly developing the stamina and skills that he needed to take photographs at high elevation and in all weather conditions.

His reputation grew enormously in 1931 after a solo exhibition at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington. The public was awestruck. Alfred Stieglitz, acknowledged as the father of modern photography, looked at his portfolio of pictures in total silence for over two hours, before finally declaring that they were amongst the finest photographs he had ever seen, and certainly the greatest landscape works.

They both agreed that straightforward, un-manipulated photography was of greater importance than pictorial techniques, with soft-focus images that harked back to oil paintings. As Adams memorably stated ‘To the complaint that there are no people in these photographs,’ I respond ‘There are always two people: the photographer and the viewer.’

By 1940, his work was now held in such esteem, he helped establish the photography department at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Masterful pictures like ‘Grand Teton and Snake River, Wyoming’ from 1942 elevated him to become a revered figure amongst his professional colleagues.

The picture draws the viewer along the winding river, to the snow-topped mountains and the atmospheric sky above. The sharp focus and vivid light he achieved left an indelible impression.

However, as World War II began to have devastating effects in Europe, his celebrations of nature appeared less relevant. The great Henri Cartier-Bresson chided that ‘the world is going to pieces and people like Ansel Adams are photographing rocks’. Other leading photographers were equally sniffy.

Nonetheless, few could fail to be touched by the elegiac glory of another of his memorable works, ‘Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico’ from 1941.The brooding view of the moon rising near Santa Fe succeeds in presenting a sight that is at once both dark and light. We see the small town in a wide sweeping landscape just as the sun is setting, and blackness descending. Only the faint light of the gibbous moon offered some illumination. The process behind this picture is revealing.

Adams was reported by a biographer to ‘have happened on the scene, rushed to stop his car and pulling out his 8 x 10 camera, and gathered the appropriate lens and filter only to realise that he could not find his light meter’.

The problem was increasingly fraught for Adams, as the setting sun would eliminate the light that he needed to illuminate the cemetery, and its white crosses in the foreground. The moment would be gone.

Adam relied on his technical skill and knowledge of exposure to persevere, relying on the added luminosity of the moon. He determined the tonal range of the various elements in the image, before choosing the exact moment to release the shutter. He would always refer to it as “an inevitable photograph.”

As an admirer noted ‘Adams approached photography as he would a piece

of music, interpreting the negative and print like a conductor interprets a score.’ Adams himself revealed that in his view “a photograph is made, not taken. The great rocks of Yosemite, expressing qualities of timeless, yet intimate grandeur, are the most compelling formations of their kind. We should not casually pass them by for they are the very heart of the earth speaking to us.’

By 1943, he was no longer fit enough to scale the rugged summits as he had done in his earlier days. Adams was not to be daunted, and simply had a camera platform built on the roof of his car. As ever, he found a way to continue seeking the best vantage point for immediate foregrounds and expansive backgrounds, and leave behind a legacy of sumptuous masterpieces.